BDD

Behavior Driven Development - introduction

As Dave Farley, one of the inventors of BDD, has said, his team was teaching TDD, but many of their students were making the same mistakes due to a misunderstanding of the underlying ideas behind TDD. This sparked the invention of BDD to prevent people from making those mistakes. To understand what BDD is and the idea behind those buzzwords, we first need to talk about TDD. I’ll show you how BDD arises from TDD.

Test Driven Development

Some people do not use TDD, which has been a part of software engineering history for over centuries (two centuries so far). Kent Beck, who is famous for writing a book about TDD, said that he simply rediscovered the idea. Imagine that at the first-ever software engineering conference, people were already discussing how the best software is developed when you repeat the cycle of writing a test, writing minimum code to satisfy the test, and refactoring.

Some peoples are writing unit tests after they write the code, but is important to write unit tests, right? … good!

Good if developer write tests right after writing the code - because he may know what exactly it is doing.

Worse if developer after writing the code goes on holidays. Then he comes back “Ahh, what was going on here?”.

But worst if developer after writing the code dies unexpectedly and someone else must write those unit tests.

The other problem with this approach is that the written code is not meant to be testable. The developer focuses on how to solve the problem, not how to write a unit test for the solution. This leads to a situation where testing may be tricky. You probably need to experience this to understand it.

On the other hand, specifying what the test should verify may be tricky too.

Look at what benefits you can get while using the TDD approach:

- Code is testable because you are writing code to satisfy tests.

- You don’t have to manually test it during writing.

- You can safely refactor your code while implementing.

But somehow some people still don’t use it. Is it so good? Nowadays, for many people, TDD stands only for “test first.” Those people, while trying to apply this approach, are writing unit tests for every class across their functionality. If all pieces work as expected, and tests are good, then the whole functionality works properly.

The real problem with this approach is the strong binding between code and tests. In most cases, if the code changes, tests must be changed too. This is a nightmare because it slows down changes, prevents refactoring, slows down new functionalities, and even worse, it can lead to having bugs in tests, and then our code will not work properly. Because it prevents refactoring, it usually leads to poorly designed applications.

As Dave Farley noticed, these problems are not directly connected with TDD. We can and should use TDD in a way that does not cause these problems. How? Don’t test classes. Instead, test modules.

Module

And what is a module then? Every software engineering guru has his own definition of a module. I especially like Jakub Nabrdalik’s definition:

-

A module has strong encapsulation, meaning that it hides its entire state. You can only change its state by interacting with the module via its public API. If necessary, the module has its own database - which is also hidden. You cannot read or write from its database, and neither can your tests.

-

A module has all layers - if we consider the MVC architecture pattern here, then the module has everything, including the frontend layer.

-

A module follows the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) and communicates with other modules. In my opinion, these two are connected, so I write them as one point here. If a module does a lot of things and grows too big, it becomes a monolith. This should be divided into separate modules that communicate with each other. A module should do one thing and do it well.

-

A module is a candidate for a microservice.

Here is how I implement modules:

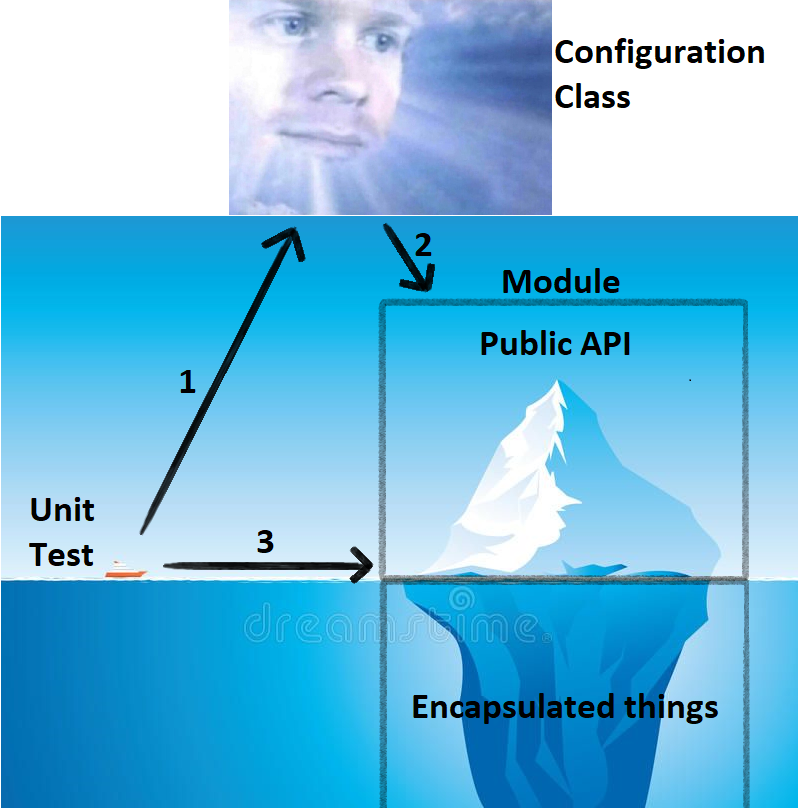

- The unit test prays to the configuration class, requesting the materialization of the Ice Mountain module, and offering mocks of the modules used by it as sacrifice.

- The configuration class creates the Ice Mountain module.

- The test code approaches the module, only seeing its public API, which is comprised of a facade class and DTOs, with everything else hidden.

Why is there a unit test boat in the picture? Because we start by defining the module through writing a unit test. This way, we will “discover” the module’s interface, and while implementing the code to satisfy the tests, we will write the business code for our module.

The facade class serves as the module’s entry point, defining its public API. The public methods of the facade class return types and arguments in the form of DTO classes. However, there’s no need to wrap Strings or Longs inside DTO classes if it’s unnecessary.

What about the DAO layer? The unit test boat needs a fast instance of the module, one that doesn’t involve I/O. For example, it could provide a module instance with an in-memory DAO, without reading files, and so on. The persistence layer should not be implemented here. In the case where we want to implement our microservice that uses other microservices’ REST APIs, I’ll describe my solution laterSee Appendix 1.

BDD

Because we cannot access the internal state of the module, we can only test its behavior. This is a crucial aspect of Behavior Driven Development, as we treat our module as a black box, since everything important is hidden. In the tests, we are not concerned with how things are done; we only verify if the module behaves as expected. With this approach, we cannot make the mistakes we previously discussed.

Unit tests only need to change if the module’s public API changes. If anything else changes, the tests remain the same. If you change anything that is unrelated to business behavior, and any of the unit tests must change, something is amiss. Step back and identify what went wrong so that you can learn from the experience. Then you can write an article about your findings ;)

If you want to refactor the entire module, go ahead! If you need to add new functionality, we will make sure that you do not break anything. If you need to make changes, modify the behavior in the tests and make it pass again.

BDD and end to end testing

Nowadays, many people identify BDD with end-to-end testing or acceptance testing. If you Google BDD, you will see articles about end-to-end frameworks. But is it still BDD? Do they first write behavioral tests and then develop code? Of course, we can use this approach, and there is nothing wrong with having your development driven by behavioral end-to-end tests. But end-to-end tests are slow! If you execute them frequently, your efficiency will surely decrease. Even worse, people may stop using those tests in the development TDD cycle, and there will be no BDD anymore. Moreover, the resulting code probably will be a mix of business logic and infrastructure code, which could lead to strong binding of your business code with used frameworks. It is bad. There is nothing wrong with writing a few of those tests at the beginning to drive your initial development if you don’t know how to start or due to other reasons. And you could still do BDD here, but please consider stopping at some point and moving to the unit tests with your work.

Don’t focus on separating your business logic from infrastructure code. Work in a way that separates them. It’s one less thing to worry about.

Don’t back to TDD

People refer to that specific usage of TDD as BDD, and have made some changes to avoid “going back to TDD” in this context:

- We don’t say we are writing tests. Instead, we write specifications.

- We don’t test the code; we confirm its behavior.

- We have limited freedom in the test structure, building tests around “given, when, then” keywords.

- And in my opinion, the key is that our tests are loosely coupled with the code.

Summary

- BDD is TDD++, when you use BDD you will avoid common TDDs mistakes.

- Don’t test classes if you want to have helpful unit tests suite.

- Write modules because they naturally bring you to test its behavior

Appendix

How define HTTP calls between microservices in BDD tests

First, let’s simplify our case. Imagine that we have two modules in the same application: producer and consumer. The relation is that consumer is using the producer module. According to our module definition, they communicate via the public API. In the configuration class of the consumer module, we must pass a reference to the producer module facade. In the unit tests, we mock that facade.

Now, let’s take the producer module out of our application and make it a standalone application. We expose the producer public API methods via REST endpoints. What happens to our consumer module? Let’s delete all the producer code apart from its public API (facade class + DTO classes). Our unit tests still compile. Obviously, the application doesn’t work because the producer module is not implemented. Now we can implement this producer module as an HTTP client of the real producer application. The implementation of this producer client module is driven by integration tests. It makes sense because this module doesn’t have any business logic.

This producer client module is a fake module. Good code doesn’t lie. Our consumer module can absorb the producer client module. Then, the producer facade becomes the producer adapter. It is important to notice that old producer module DTOs became part of the consumer module. From this time, they don’t have to reflect the real DTOs of the new producer public API. Necessary mappings should be performed in the adapter implementation. From now on, our compiler is no longer checking if the consumer application integrates with the producer application. The relation between them should be described by contracts, and it should be verified via contract tests (you can learn about contract tests in my other article on Contract Tests).